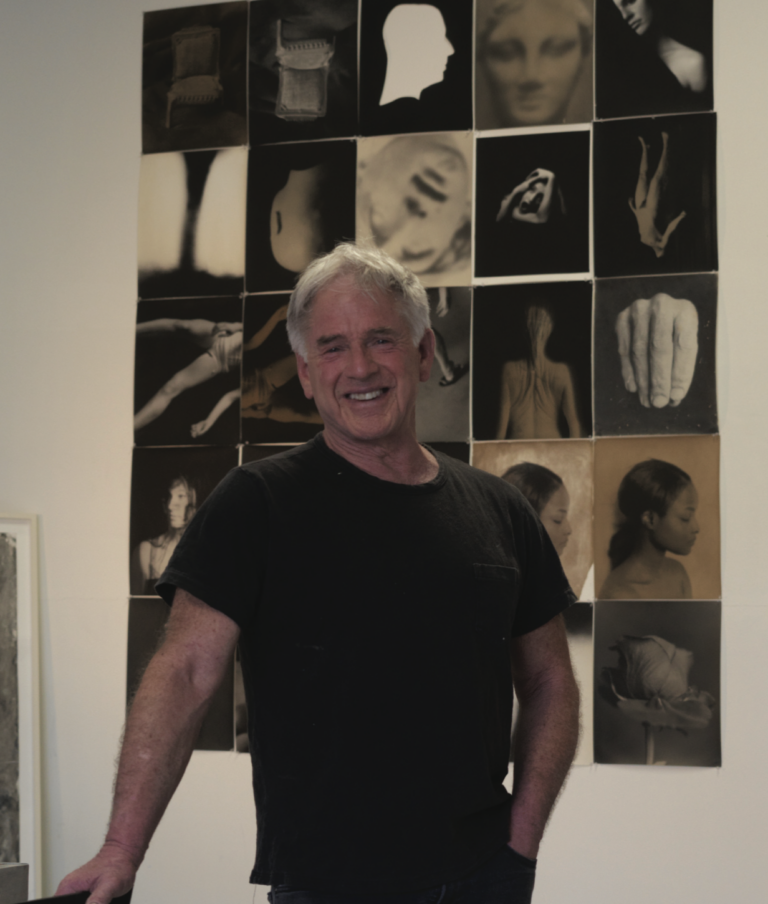

HE IS A VISIONARY, A SAINT, A SINNER, AND A CINEMATIC KAMIKAZE. He was a Christian Brother until he was 28.

He ignored convention from the beginning. (He flunked kindergarten.) His experimental documentaries have changed the grammar of movies – he introduced time lapses, for instance. He is most known for his Qatsi trilogy, Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi, and Naqoyqatsi.

But his through line is of another dimension: We are out of balance, we are separate from ourselves, from the world. We are ourselves an out-of-control virus. The way to find hope is to start off being hopeless, to confront generally and precisely what is now.

His governing metaphor is that movies themselves are constructed using negatives, but the final result produces a positive.

Reggie is eloquent. His words and work are so crystalline and pristine, it’s as if he is channeling from another world, and has granted us admission to what he sees. Sometimes, in our conversations – and in his movies – I have no idea what he is talking about.

Ultimately, his overriding vision is painful to take in.

But he can be a joy.

He tells me he’s a great dancer. I believe him.

You describe your latest movie, Once Within a Time, as bardic. What do you mean by that?

The bard is one who cannot help but feel and fear the suffering of others. I make films, not entertainment. That’s why I’m an outsider, or out-saned.

I don’t even know how to categorize the things that my colleagues and I have done. And what I do in all the films, especially Once Within a Time, is try to offer a fantasy of the real, not a fairy-tale. Fairy-tales have laudable moral implications created by adults for children. Big booga-boo, the holy saint, whatever, and then happy endings. This has none of that; it’s a fantasy of the real – that’s what bardic events are. They’re the things that got prophets into trouble. Prophets don’t tell the future, they talk about how the future is in the present.

So this is a bardic tale where the ending is not a happy ending, but a resolute beginning. It leaves you with a question: Which age is this, the sunset or the dawn? It’s a question that only the universe may answer, but being animals, we may answer those questions if we are heroes, if we resist destiny, if we are willing to leap into the vivid unknown. So that’s what bardic is. My films are bardic documentaries, actually.

In your films, the subject is unspeakable. It’s not an event we’re waiting for, it’s a black swan event that’s already happened.

We’re living in the middle of it. We’re on speed in rush hour, outrunning the future, we’re in a state of shock, we’re on the clock, the digital shower we take every day, our fingers touching over 30,000 keys a day. We’re burnt up, we’re hot.

This is a way to quell the heat through humor. Not to resist showing the tragedy, but to quell it through humor. Humor is who we are. Baudelaire says humor is the stigmata of original sin.

You have said that the way to be hopeful is to understand what is hopeless.

Let me explain it in terms of the verb. The verb is children now, not in the future. They become the future, but they are right now, they are embedded in destiny, and they know destiny may not be overcome. So if they are courageous enough to be hopeless about this world, then they’ll have the boldness to be hopeful about creating their own world.

The world we live in is homogenized. So centralized that it’s cracking apart. It’s a square cracking to a numbered code, and we’re all buying it. It’s the price we pay for the pursuit of our technological happiness.

WANT TO READ MORE? SUBSCRIBE TO SANTA FE MAGAZINE HERE!

Photo SFM