ONCE UPON A TIME, most serious photographers did their own printing. It wasn’t just the legacy of greats like Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. It was a commonly held belief that a big part of the discovery in photography occurred in the development of film – in the darkroom.

And then there was digital.

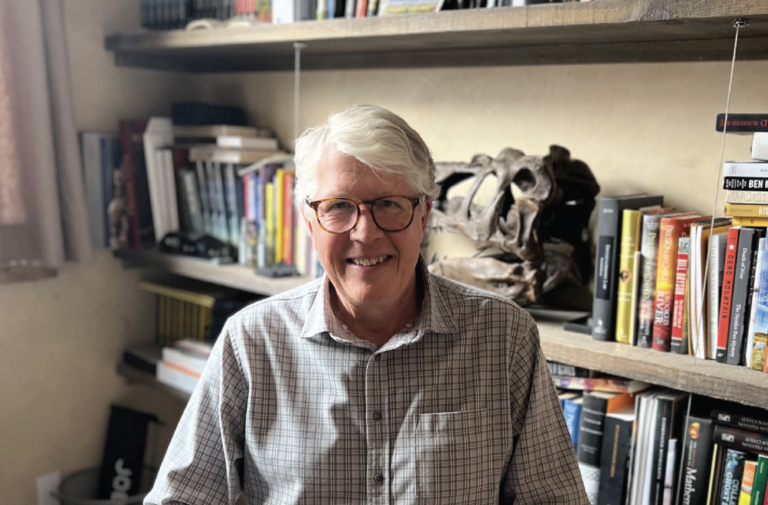

Thankfully, there are artists like Robert Stivers who haven’t given up the darkroom ghost. The results are unique; his pictures seem to “suggest spiritual visions,” as one reviewer noted.

For Stivers, the darkroom is a source of inspiration, creation, and improvisation. Happily for all of us, his work is not just extraordinary but is also recognized by places like the Met and the Getty. Artistic talent and acclaim don’t always live together, but it’s nice when they do.

How much of your art is done in the darkroom?

At least is 50%. It might actually be 90%. When I walk into the darkroom, I probably have a fairly commonplace negative. The challenge is to transform it into something that gets somebody’s attention. I want to make something compelling, but I may not know exactly what that is. And it often changes during the printing process. I’m very improvisational, spontaneous. I don’t do test strips when I’m printing; I just grab a sheet of paper and expose it.

Last night, I had a very underexposed portrait that I wanted actually to print dark, so I thought, Ah, this didn’t work. Then I thought, I’m just gonna go with it anyway. So I let it go as far as it was gonna go in the developer. Sometimes I put it back in the developer and it just goes completely black, but sometimes I pull it out just in time, stop it again, and then there’s something.

I have an idea of what’s gonna happen because I do it all the time, but most of the time, it doesn’t really work. Like the next day I look at it and think, Well, that didn’t work.

Is there a decisive moment in capturing an image?

I think there are many decisive moments.

When I started, I shot everything sharp. By the late 1980s, I thought, What happens if I still shoot with a square format? What happens if I make it rectangular? And then I thought, What happens if I throw it out of focus? And when I did that, I thought, Well, this is really fantastic. So for 15 years I threw everything out of focus.

I was intentionally throwing something out of whack. Like, if you have a stereo system and think, What does Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 sound like backwards? It was an intentional switching of something that we are taught to appreciate.

Is there any time when you feel you’ve nailed it after you finish an image?

Not really anymore. That would be so nice to have a sense of completion like that. But I think I often feel like, Well, that was successful. This really works.

I can make an image work in many ways. It’s like the sacred and the profane are not just two possibilities, but a lot of different possibilities.

So light goes on in the darkroom, and that’s when you really know what you have?

No, I cheat.

I cheat all the time. To be honest with you, I expose it and put it in the developer. I don’t use a stop bath because I want to be able to still play with it. I just run some fresh water on it so it’ll hold for a little bit. Then I turn the light on and say, What do I have? I have a few seconds to make a decision. Do I wanna put it in the toner? Or do I wanna put it back in the developer and have it go crazy? Or do I wanna put it in my bleach bath, which will make it disappear? That I find really intriguing. To watch a beautiful image disappear is pretty amazing.

Learn more at robertstivers.com

Photo SFM