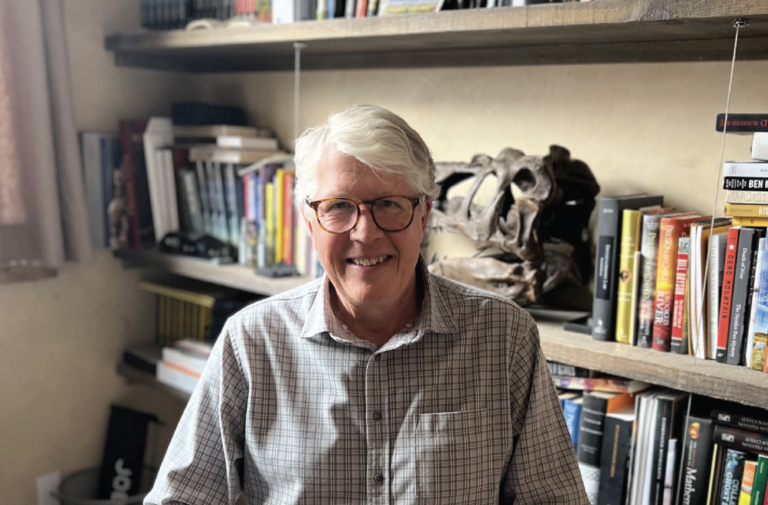

HE GRADUATED FROM PRINCETON without the remotest idea of what he was going to do next. That made him different from his classmates, who had it all planned out, or whose parents had it all planned out.

Today, John is still different. Now he guides others who seek to know more about their place in the natural world. His personal development work employs therapy and, sometimes, plant-based psychedelics. He has immersed himself in the subject. When you meet him, you feel his openness, vulnerability, and compassion. And modesty.

During our visit, I asked him if he was optimistic at heart. He said, The earth will be fine, though maybe not all the people on it. But he believes we are at an inflection point and that there is positive change afoot.

What is your first memory of Santa Fe?

In 1986, I connected with a couple who had a place on Canyon Road, and they had these dreams of a tribe of people coming to be with them. So I hung out for a while and did walking meditation, hiking, sweats, and some drugs like MDMA. I experienced this place as the land of enchantment. I felt the magic of this place.

Six of us went up to Aspen in the fall. We rented a house there and started leading workshops. Our introductory evening meditation was called Spacewalk, and we’d do a guided meditation, taking people around the solar system, connecting with the energies of each of the planets. That was an introduction to our weekend workshop, Lift-off, which was a smorgasbord of things, including a sweat lodge and male-female dynamics. We did mask-making – we’d put random music on, and everyone would create a mask.

In 1988, I moved to Santa Fe with my son Michael and his mom. I was involved in macrobiotic food and the café Planet Earth for a few years.

In your personal development work, you advise and talk about higher consciousness and plant-based psychedelics.

I started bringing people here from South America to lead ayahuasca ceremonies. There’s a guy from Brazil named Carioca. He’s one of the best-known people leading Brazilian-style ceremonies, so I brought him here a number of times. The Brazilian tradition is pretty interesting because it’s an amalgam of the Portuguese Catholic, the indigenous Amazonian, and the West African.

I’m a child of the ’60s, so I tried all the different medicines. Today, ayahuasca is a mainstream traditional medicine people know about. I appreciate people who connect with the traditional indigenous forms of ceremony with plant-based medicines. And these medicines have evolved to microdosing mushrooms and LSD.

What do you learn from indigenous ceremonies?

I think there’s a resurgence of respect for indigenous wisdom and the indigenous understanding of our relationship with the earth.

Certainly, when you look at what’s going on in the world, and then you sit in ceremonies like these and feel the connection you have with spirit, you start to recognize the power of connecting with others and with the natural world in a benevolent, cooperative way. It is very different from what you see in Western culture and the effects of capitalism and greed.

So it’s about spirit and connection?

That’s one big part of it. The other part is understanding the value of these natural medicines.

Paul Stamets is an advocate of psilocybin mushrooms; his writing on the mushroom’s role in the evolution of this planet, the role that it plays in the forest, is critical. The mushroom is actually connecting nutrients between different plants. Those connections are the same things they do to our psyche and our hormonal system. It’s networking, creating more balance within.

I respect the culture of people that have gathered around these traditional medicine circles. Their wisdom doesn’t necessarily come from years of studying books and whatever, but it comes from tuning into what ultimately is available to all of us to access if we go within.

And people are becoming more open to this. For example, ketamine is now regularly used for treatment of resistant depression. There is a ketamine program at Ten Thousand Waves here in Santa Fe. And Oregon just legalized psilocybin therapy.

Sometimes medicines just open you up to things that have been buried in your psyche. One of these medicines that is pretty interesting comes from the glands of the Sonoran Desert toad, Bufo alvarius. It’s a big toad that hibernates for nine months a year underground and lives in southern Arizona and northern Mexico.

The experience is not a long one, but it’s basically an ego reset. When you’re in that beyond the threshold space, you lose all sense of self and order. You’re just in pure consciousness, which has many different flavors. I personally have a blissful experience, but I’ve witnessed friends who’ve gone into deep grief, anger, or frustration. There’s a period of five minutes or less when you’re in that place. You gradually come back and become aware of your body. Then, for the next week or so, you have recurrences of this space. There’s a lot of work to do to integrate some of the things that come up during that experience.

All of us have experienced childhood trauma to one degree or another, and this can be triggered by medicines. But you still have work to do to integrate it and heal. The medicine doesn’t do that for you.

There are too many people who bury stuff that’s happened and don’t want to deal with it. But it always comes out in some way. I want to normalize that kind of healing work. And there are so many different ways and methodologies to help. Medicine is only one path. But that is something we all need to do – to find our fullest and truest expression of who we are.

Learn more at johnmeade.net

Photo SFM