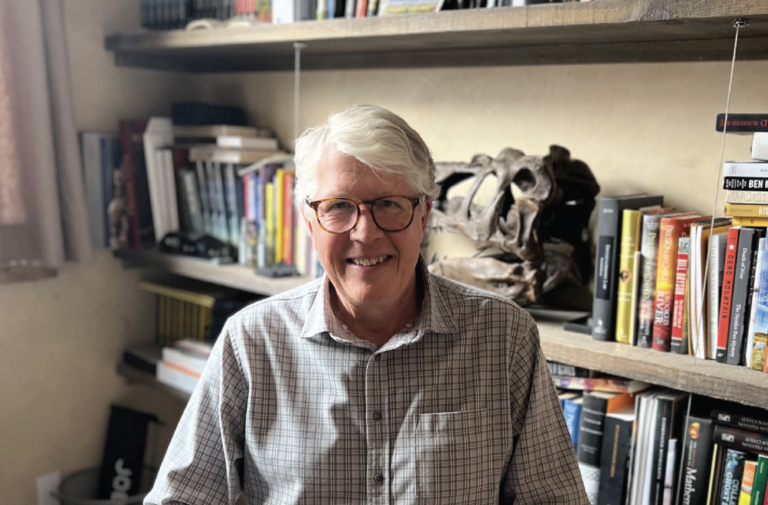

THE SPAT BETWEEN FITZGERALD (The rich are different than you and me) and Hemingway (Yes, they have more money) seems a little shallow when you’ve spent time with Sallie Bingham.

She is a reluctant authority on great wealth. She grew up in it – in Louisville, Kentucky, a daughter and heir to a family newspaper fortune. When she and the other women on the board of the company were fired from the newspaper, she spoke up. That rebellion prompted the sale of The Louisville Courier-Journal. Under the Binghams, the Courier-Journal won eight Pulitzer Prizes, establishing the newspaper as one of the top in America. (And this in the halcyon days when a big newspaper was worth a great deal of money.)

That triggered a book, Passion and Prejudice, of which Gloria Steinem said, For the first time, a gifted writer born into a family of inherited wealth and power takes us with her behind the doors of that patriarchal hothouse. [This] is a major step toward feminist change and democracy. By her courage and example, Sallie Bingham already has inspired women in powerful families to begin to revolt.

Balzac got it right: Behind every great fortune lies a great crime. In this case, it may have been what her grandfather did. And she told that story. But what Sallie got in return was her life as a truthteller, a writer, an artist, and as a stalwart supporter of women’s rights. With a strong Southern accent, she is both funny and charming in a way that sometimes seems from a distant past, a distant land we heard about, but never saw.

Sallie has lived in Santa Fe for 15 years and given countless contributions to our community. If I hadn’t asked her about it, she wouldn’t have mentioned it.

What made you have the courage to write a book that revealed so much about your family?

It was horribly difficult, because at that time we were in the midst of the sale of The Louisville Courier-Journal. Everybody was furious at me because I refused to resign. And my brother, the publisher, asked all the women who were newly elected to the board to resign. That included his mother, his wife, his two sisters, and his sister-in-law.

But I said, Why should I resign? That led to two years of horrible disputing and carrying on and threatening and raging. After I came through that, I realized that really this family is impossible for me. It’s always been impossible, but it’s more impossible now because I really am committed to telling the truth. And they don’t want to hear the truth.

I’d taken my mother out to lunch. She was furious with me, like a stone. We made some small talk. And then eventually when we were on our way out, I said to her, I’ve got a contract with Knopf to write a book about the family. And she looked at me and said, If you mention Mary Lily Flagler, I will never speak to you again. Well, why Mary Lily Flagler? That is the source of the money. And that’s the reason. That my grandfather almost certainly murdered her is another fact that nobody ever wanted to admit to.

Your grandfather married Standard Oil’s Henry Flagler’s daughter?

Yes. Robert Bingham was my grandfather. He came to Louisville, tried to get into Democratic politics, ran for mayor, was not elected, was a lawyer, but not very successful. So things were not looking really great for him.

Then the news was all over the country that Flagler had died and Mary Lily was now the richest widow in the US. He was playing poker with his buddies, and they said, Rob, didn’t you know her when you were growing up in North Carolina? She’s now a young widow with all this money. Why don’t you go down there to Florida and court her? So they bought him a suit and bought him a train ticket and sent him down to West Palm Beach. And within two or three weeks they were engaged. The papers called him the ‘Cinderella Man.’ My mother wouldn’t want me to write about this. You can’t admit to the source of the money. As you know, all great fortunes are founded on a crime.

My mother never spoke to me for the last ten years of her life. And my father never spoke to me again. They tried to disinherit me. They couldn’t because of the way my grandfather had set up those trusts, so you can’t disinherit anybody. Otherwise I would’ve been penniless. But nobody wants to get to the end of their parents’ lives and find they won’t speak to you.

But as a committed writer, if I compromised and said, All right, I’m not going to mention Mary Lily, I really would not be able to go on writing. I really felt it was my whole career that was on the line. And families that encase a lie like that, all the kids know there’s something here that’s being hidden. Because there’s a sense of secrecy in the end. You don’t even know what questions to ask, but there’s something hidden. What is hidden here? What is it that nobody’s willing to talk about? Do they feel so guilty they can’t bring themselves even to mention it? You don’t forget that sense of the secret, the secret that nobody can mention.

And so you wrote it and all hell broke loose.

And all hell broke loose. My mother hired a team of lawyers, it’s supposed to have cost her a million dollars. It was extremely hard to combat because Binghams were well-known; they were authoritative.

I’ve struggled with this all these years. What mattered to me was my own integrity. It’s a shame that it had to result in that bitterness and estrangement, but still, when your integrity is on the line, if you give up on that, you might as well just go to bed for the rest of your life.

To paraphrase Mark Twain, It’s just much easier to tell the truth because you don’t have to remember it. So that book freed you and allowed you to pursue women’s causes.

I was an 11% shareholder, so when they sold the paper, they couldn’t prevent me from getting my share. It was about $60 million which was a hell of a lot of money then and now. So that allowed me to use $10 million to start the Kentucky Foundation for Women, a nonprofit that I started in the late 80s, which is a small private foundation, but it gives out about $250,000 a year to Kentucky artists and writers who dare to call themselves feminists. It’s just enormously helpful and important for artists. And I think we’ve done a lot of good work over the years. It’s not called the Sallie Bingham Foundation, it’s called the Kentucky Foundation. Because it’s not about me.

You also wrote a book about Doris Duke, the tobacco heiress, who was called “the richest girl in the world.” Her philanthropic work in AIDS research, medicine, and child welfare continued into her old age. Did you identify with her?

I appreciated the fact that she lived with an enormous amount of scrutiny, disapproval in the end, tried to hide from reporters because she felt they would never tell the truth about her. They just repeat all the cliches, that she took her shoes off. She took her shoes off in Del Monaco’s and what a scandal that she didn’t have her shoes on! She never benefited from an education and I benefited enormously from an education. Her mother didn’t want her to have an education, so she basically had about an eighth grade education.

She was considered outrageous, but outrageous for what reason? Because she did what she wanted to do, didn’t commit any crimes, she was married twice. So what? I’ve been married three times. So what? How can you make such a huge scandal out of someone who was – I don’t even want to say eccentric– someone with unusual behavior in that period?

But no one could accept her for who she was. She was very free with her money and gave away enormous amounts and created the Doris Duke Foundation — something like $1.3 billion, a huge endowment. Nobody knows about it. They know about Rockefeller, they know about Ford, but nobody ever knows about the Doris Duke Foundation.

The occupational hazards of growing up in this charmed world.

That reminds me, my mother, when she was really aggravated with her five grown children, used to say, You are all beautiful, you are all rich, why can’t you be happy? Well, you’re not happy because there’s no love, it’s just as simple as that. And no matter how much you have and how privileged you are and so on, if there’s no love, it doesn’t matter, it’s just dust.

Why does that so frequently happen among the very rich? Forgive me.

Yeah there is a through line. In my family, there’s been nothing but a series of horrible disasters of these men in the family dying young in ghastly accidents and so on. It all goes back to the secret. When a family has accumulated a lot of money over three or four generations, the kids want to know why, but the secret can never be divulged. And so the way you stop the kids asking is by withholding love. Shut up, say nothing. Don’t notice, close your eyes.

So you don’t want them to be curious. And that’s lethal. You know?

Your book Little Brother describes what you call your “dreadful list” of nine close relatives who died by accident, suicide, overdose, exposure to the elements, and electrocution. It focuses on your youngest brother, Jonathan.

It’s an attempt to get out the truth, of what happened to him and why it happened. He died in 1963, so you can see how long it’s taken me to get to that. Because I felt that this so-called accident, this suicidal accident that he engaged in, really was the direct result of what he had learned growing up. It was about being privileged, so privileged that you can be utterly reckless, and it doesn’t matter because there aren’t going to be any consequences.

Maybe it’s not a curse, maybe it’s a feeling of recklessness?

Anything’s possible, that’s right. Anything’s possible. You can drive 100 miles an hour and you’re never going to crash.

Is this what Jesus meant about the camel and the eye of the needle?

Yeah. He’s right, because even those of us who are enormously generous and give away a lot of money, we still can’t overcome the basic inequality. You know, why in the world do I have all this money? Well, I can give a lot of it away. I do give a lot of it away, but there’s still basic inequality there that can’t be erased.

How would we ever extract ourselves from capitalism? It couldn’t possibly be done. The only hope is — and I do see this a little bit with younger people — a return to not being that interested in owning things.

What is the role of local newspapers today?

I think they’re crucial. Crucial. There was a time when newspapers bound the community.

We don’t have the impact of the churches or Lions Clubs, or Elks, or Women’s Clubs as a way of binding a community. Communities don’t self-bind. We don’t know how to do that. Newspapers can do that. Maybe your magazine can do that.

Photo SFM