I WAS A BIT RAGGED when I showed up to talk to Gasali. Most of us have volatility in our lives, when little stuff in our day is a little off, fickle, as it were. I am not talking your worries about the new cold war. I am talking about when the lights turn red when you are already late to getting your kid to school. I don’t remember what it was that day. But it was like that and it all began to change slowly and then all at once, in the presence of Gasali.

It really is presence, some alchemy of calm and voice and eloquence and stillness, a way that has its own way. It had the power to transport this editor to a much better, happier place. (Why hadn’t I come earlier?)

Before I met Gasali I didn’t think much about cloth – where it comes from, what goes into making it, what the patterns mean. I certainly had never contemplated cloth as something that identifies a person, a family, a place, and a belief.

But that all changed when Gasali began talking.

I hope you read this. Because, on that day, maybe all the lights on Jaguar Road will turn bright green, just at the right time.

You teach the traditional Yoruba techniques of batik, Adire Eleko and tie-dye using an indigo vat and cassava paste resist.

My mom was an indigo dyer in Nigeria. She used cassava, or Adire Eleko. Adire is the natural fiber. A lot of artists in my country call it recycle, coming from scratch. Because we don’t need capital like money to buy a lot of things because cotton grows in my own environment. We have the fibers.

Indigo is grown wide in my own community. In art we use cassava, tapioca, which we also eat as a daily meal. My grandparents also painted with it, as a resist to create a design into the fiber.

I see this fabric on my grandparents because when they wake up in the morning, they like to chat with neighbors on the balcony outside when they’re brushing their teeth with a little piece of stick from lemon tree. And then when you see that cloth on them, it will be this tapioca Adire cloth. And they wrap it around them like your bed sheet. Because the weather back home can only be around 60 degrees in the morning. So it’s a little chilly. And then they lay them on the bed in the evening before they go to bed.

My grandparents of my mother’s side, they do the healing. I saw my mom, growing up as a young kid, as a midwife. They relate to power of the spiritual and then the clothing. Back in the olden days – I was born in 1970 – I didn’t really take all this serious because when my parents do all this with fiber, they want to make sure you pay attention, but I kind of prefer to go play soccer.

Where do the designs come from?

There’s a lot of connection between the artistic and spiritual purpose. That’s what I teach when I travel all over the globe to give a lecture or workshop. This design you see right here, is a symbol, it’s a motif, it’s a part of the life we’re living every day.

And in religion, we practice in the whole environment like God of lightning, God of iron, God of rain, God of wind, God of ocean. All those things come across to the design. And this is what we carry instead of identification cards. When I came here, I didn’t know you need your identification card when you travel, because back home in Nigeria, anybody see me with this blue shirt or my blue indigo hat, oh he’s a Yoruba man. That’s my identification.

So when I came to this country, I told people, when you see somebody walk in front of your door, if they’re a mechanic, how do you know? The way they look, and it’s the fiber of their mechanic. If they’re nurse or doctor, you can tell. Oh, he works in the hospital because of the cloth she or he put on as a nurse, you know what I’m saying? It’s the fiber.

And the cloth never die. Even when the person who wears that cloth, they pass on, they left the planet, but the cloth still live with them.

It falls apart because the person, because in my tradition, we believe in our own dreams. When you dream about someone, it’s also the cloth. When somebody passed, like my grandparents, they say, Gasali, can you take this pant? Can you take this short? When people left, in our belief, everything they own here, they took with them by spirit. And then, when I sleep, when I dream about them, you see the same fabric on them. And they give it to you. That is why people freak out like, Wow, they just gave me this cloth last month. How come it rip? Because guess what? You not the only one who wear it, you share it with somebody.

What’s your process?

I start with cooking the cassava. We call it Lafun. I make like a little paste, like a jelly. So when they cool down, I apply. And when I paint it, what is my tools? I use the chicken feather, small broom and a small knife as the tools to apply this design. People say, Wow, you use a chicken feather, it’s like a brush. And that is how my grandparents, my mom teach me as a tradition. So that is where we put the cassava. But when you look in the back, it only resists certain parts.

People see my piece sometimes when they visit my studio. They say, Oh, how come you don’t want to sell this to me? I say, The reason why I don’t want to sell it, I don’t know if I’m gonna be able to make piece look like this again. So this is belong to museum. That is where it’s gonna go. I hold on to it, but not for money.

And money, like smoke, disappears.

It disappear, and the piece is gone. It doesn’t matter how much you pay for the piece, how are you gonna treat the piece you have in your hand?

WANT TO READ MORE? SUBSCRIBE TO SANTA FE MAGAZINE HERE!

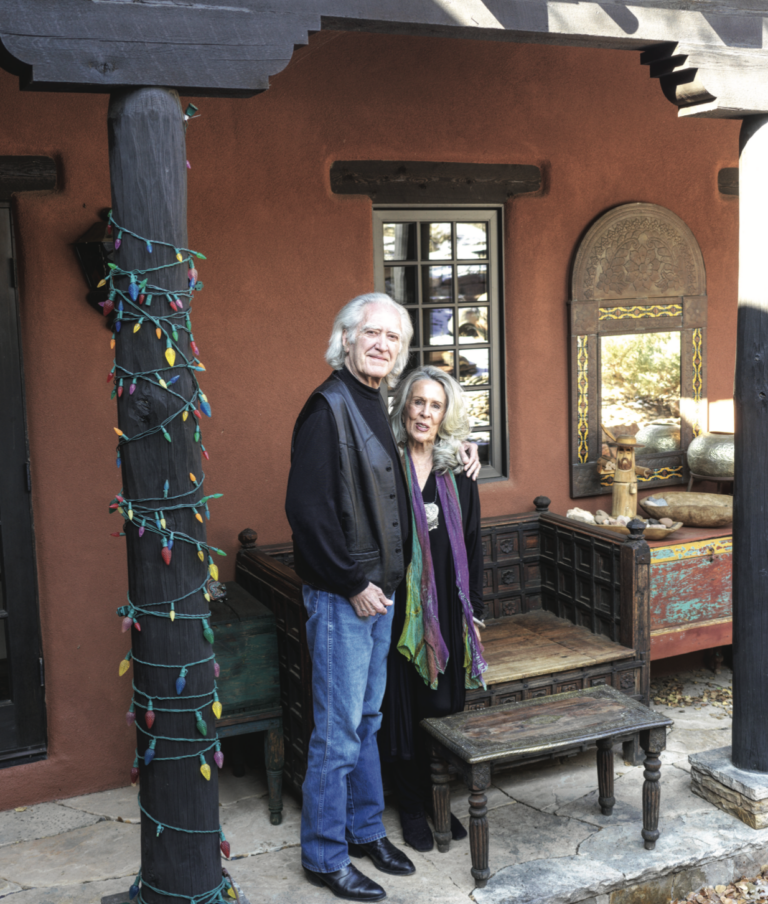

Photo SFM