I WENT TO SEE WILL on a bright day between Christmas and New Year. He is a blacksmith.

Let’s have a little holiday cheer to start the interview. I don’t know if you partake, but…

Good idea, I absolutely do partake. All my compatriots are on their holidays. So, you’re taking time, I’m taking time; we deserve it.

Okay, so I’m gonna give you this horseshoe while I get us a glass. But you can look at this, and you can read what this says. This is very delicate. This was from a family member, Joyce Whittier in the 1970s. It says, This tiny horseshoe was made by my father, John Wood, about 1894, for his sweetheart, who later became his wife, our mother, Laura McPhee. They were married April 30th, 1895. My father was a blacksmith. (Signed) Winnie Wood Whittier, December 20, 1962.

So that’s when this note was written. It has been updated October 8th, 2013. And it says, A gift from Joyce Whittier Chaplin.

It was To Willie, which is what I used to go by as a young lad. So it’s a tiny, tiny articulate piece of paper. It was given to me in a little Vogue perfume case when the ladies would go around door-to-door, probably, selling makeup and such to the ladies. But this was the horseshoe.

This is the remaining estate that I have been able to possess from all those years. But probably one of the more significant in my life in terms of poignancy.

This note allowed me to recognize that by somehow figuring my path out in life as a young man trying to develop, that I had somehow successfully stumbled into an arena that was the right path, man. Whether you call it walking the right path, the narrow path versus the wide path. But it allowed me to say, well, I must be on to something.

You made a commitment to learn the craft and the art.

I was working in forestry and my main source of transportation was hitchhiking. I was poor.

I had no initial investment from my family or anything like that. Parents separated, left to stray at 14, 15, so I was hitchhiking in Nova Scotia. That’s how I got around. And I was coming back from a job that was horrible. And two guys picked me up who were welders. This was 30-some years ago. I knew it was dangerous, but you could meet interesting people and hear stories. Sometimes there were elders that would give me a few tips. But anyway, these two welders picked me up, and they said, well, you should consider learning to weld, be a TIG welder. We eat steak, is what they said.

What?

Welders eat steak, meaning they make good money. They said, you’ll live better than what you’re doing. But honestly, the craft drew me because I was just tired of hitchhiking around, being a broke-ass kid. So I went to the library, because that was the only source, right? I went to the Halifax library, and I was looking for a book by Jack Andrews, Edge of the Anvil. And it was checked out.

So then I looked for an apprenticeship with somebody in Nova Scotia, a man named John Little. And I went in there, and he asked me to forge a nail, which is the simplest thing, and it came out the most crooked, bent up piece of metal. And he just basically said, I can’t afford the time to teach you.

I wasn’t finding anybody that would allow me to work with them. Everywhere I went, I would set up a corner of the garage and make my shop, do tinkering.

Then, I landed in Santa Fe and I started working for a gentleman named John Prosser. At that time, Santa Fe kind of had a little hub of iron workers. It was small, but a lot of them were craftsmen before they were pipe welders. So, I worked for John Prosser. He had a fully operative blacksmith shop that had beautiful power hammers, beautiful investment, good clients outside of Santa Fe. So, I worked for him, but not long. I would’ve been about 27, and I had acquired a certain number of tools, but not many.

Then came an opportunity. There was a metal worker who was going back to Switzerland, and he had a small shop, a live-in space. I had no money. I had some tools and I just struggled through it. I wasn’t a legal citizen of this country, I was from Nova Scotia.

Then, I had a son here. He’s 18 now. So that drove me to stabilize and stay on the path. I had little formal training, but enough to know that you can do anything.

What made you want to do this?

When I was a boy in the country, we liked edged weapons, knives and swords. I grew up on the farm, with a lot of implements, scythes and sickles, and washed my grandfather’s shoes and horses. It’s just such a good material to work with.

Especially forging. Welding and putting things together is pretty cool, you have a hot glue gun, but the forging, taking, like, a square block of steel and through the element of fire, changing it through the pressure of the hammer and the anvil, moving that material in a distinct, maybe artistic, maybe utilitarian way is a fascinating thing.

Walk me through how you do it.

Right, so for the temperature of mild steel, 2200 degrees Fahrenheit is yellow, it’s malleable. Like wood, steel is fibrous, and has grain in it. Carbon or nickel have different amounts of grain and will change the composition to make it harder or softer. Forging and shaping it with that heat is interesting and challenging.

And your primary tool is what?

Hammer and anvil. I have a hammer and anvil here, old school. But a power hammer for somebody that’s doing any amount of forging is gonna save your arm, you can’t just stand there and hammer on stuff all day. You get tendinitis in your wrist and all kinds of things. So, that thing, that power hammer there is a godsend. They’ve been around forever; the water wheels that people would set their shops up next to would have big old held hammers, driven by the water, and it was on a long arm, pounding on an anvil, and it would rotate, and you would have a pulse to your forging process.

1 0 1 They’re standard processes like drawing out, flattening steel, squaring it up, smashing it down, pushing drifts through holes to enlarge them. It’s just a matter of how big of a forge and how big of a hammer and anvil you have in terms of what work you do.

Is it lonely work?

Thank God for Quinn, my apprentice. Oh man, in so many ways we get along so well. But yeah, it can be an isolated experience.

It’s not like working in an office. I could never work in an office. I could never work for anybody. It didn’t seem very good. So, I’m not bothered by being alone working. You’re intrigued when you’re in your mind and your craft. I think you’re good with it. Meeting maybe new people, friends, you must go out of your way to go out into the community. But there’s no talk around the water cooler in the office.

What’s a day in your life look like?

I usually get up about 5 o’clock, get ready, get my everyday carries together, pack my truck, pack my lunch, ship off to the shop. We convene and start here at about nine and work till five. And through that day, I jump around from job to job.

So depending on if we’re in the shop working, we’ll come in. We have our items laid out. We have our fuels for heat and everything ready. Quinn will assemble, measure, layout. And once we have our parts, they’re forged, they’re cooled, then we start creating.

I’ve read courses on blacksmithing are becoming popular.

Maybe it’s generating attention at this point. There’s more of us, our ideas are communicated faster now.

But if I judge it correctly, people are still in their offices, in their cars, in the shopping mall, the grocery store, in front of the television. But this trade demands interaction with items, heavy items. I think they’re missing out on being physically engaged in their work.

Understanding that you can take something that’s so hard and make it so soft and malleable, and create something that is utilitarian and functional in a human’s hand, is a most indispensable material and experience. And I think the more we sit and watch things happen on screens, the more we lose that hand-to-hand combat, so to say, with the material world, right?

Is legacy important to you?

Legacy in one way, and permanence in another. I mean, it’s not like it’s likely this steel in the current form is going to change.

These become living relics from the past, and I think that is significant for people in the world, whether they know it or not. Like with family, you should be wanting to make a good impact while you’re here. A man from Baha’i Faith picked me up hitchhiking once, and he said to me, The mantra goes leave it better than you found it. Right? And I think if you can leave something good behind, that’s important.

Well, and I think it’s good to understand that we are not of this world. Right? We’re here to do work. Our yearnings and our desires and things here shouldn’t be what drive us as much as our spiritual growth. You will leave it all behind. It is a destructive force, these things we have all have appetites.

So, it’s best to understand that we are temporal here. But I think, at the same time, you want to leave some footprints in the sand, if they’re good. What we’re challenged with now is we’re seeing all these footprints and tracks in the wilderness. I don’t know how we feel about what we’re doing daily, or if it has any significance at all to some.

You’re a very tactile person, right?

The steel is tactile, you want to touch it with your hands. You have to be a tactician because you’re going to use the anvil and the hammer to create compression in it. And you are the iron, it is an extension of you, the tongs and the hammer. One of my favorite movies growing up was Conan the Barbarian.

Not only because of his attribute of the character of the warrior, but also his father was a blacksmith, right? The God they worshiped was Crom and he lived in the earth and was the blood of the earth, but it added a nice element of the mythical.

Conan was Arnold Schwarzenegger. He was a very strong figure. He was a person that was kin to hardship as well, right? These people were not living easy. It’s just a great tale.

That gave me insight into what this substance was. We come from the north, we are descendants of Scotch, Irish, Norwegian people. We made a utilitarian tool of defense, but also with a sense of righteousness and good and bad in it.

So steel came from the spirit of the earth?

Iron is red. It rusts and it’s the blood of the earth. The steel is the carbon within us and how we decay is the same as steel is accelerated in fire. It is like a skeletal structure that we’ve drawn from the earth. They say oil is the blood of the earth. I say the steel is the strength, the material that we draw from the earth and we refine it and then we build buildings and airplanes and everything else out of it.

Is most of your work custom?

Yep, it’s all custom. I have my fancies and the things I like to do, but it’s all commission – railings, fireplaces, lighting, exterior gates.

Do you like what you do?

I love it, it’s everything in my life.

Do you think of yourself as an artist?

I’ve never marked any of my work with a maker’s mark.

Why?

I think a little bit it’s a letting go of the ego. We do notable things and they’re good, but I would probably lean more on the end of a craftsman than an artist because artists are expressing their souls with a painting. Blacksmithing should be like we are here – we are quiet, we are strength, but we are not loud.

When we started talking, you showed me the horseshoe from your father. Why is that so important to you?

He couldn’t afford a diamond ring for my mother. So he made a small horseshoe for her. It’s an endearing piece of history, but I think it’s important to me. It’s one of the last things I have from my father. But again, it doesn’t say you’re the best; it says that you have a natural hand. I think that’s what they were saying to me — Go follow, follow through. Keep going.

This is sort of in your blood, right?

I have a book in the truck I could show you. It goes back to Scotland. We’re seven generations down, not everybody was a blacksmith, but a lot were.

What about Santa Fe do you like?

This is a wilderness in a way. There’s a civilized artistic eye in the township, but I’ve always loved the wild. Here there’s enough of the wild and there’s enough history buried beneath it that you can just lose yourself. It’s very good. That’s not in every town.

We’re slightly rippling and wild and you can go two ways with that, right? You can fall off the edge or you can refine that sort of wanderlust nature in yourself and funnel it into something. Some people are into music, photography, cinematography, fabric, but this town has allowed us a great deal of growth, personally. I don’t go into town proper that much. There’s not a whole lot that I need there. I’m happy other people like to come and see it and witness it and experience it. The best place I can experience it is in the mountains, on my horse, riding, doing things.

Learn more at IronwoodForgeSantaFe.com

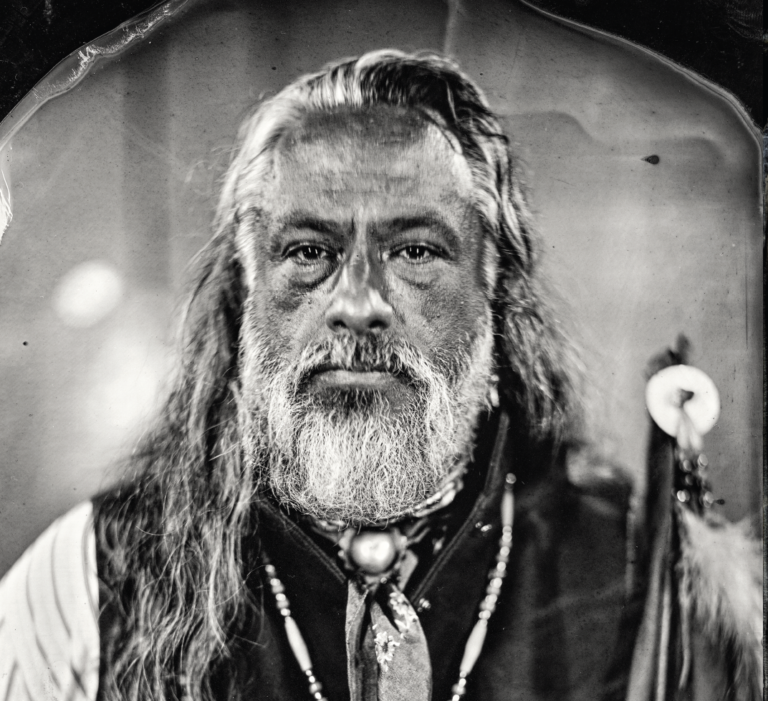

Photo SFM