LISA LAW HAS A GIFT for figuring out who’s in and what’s cool. She was there at Yasgur’s Farm, Forest Gump-like, in 1969. She had the vision that the hordes of flower children arriving at Woodstock Festival might well forget to bring enough food. So she and the Hog Farm Commune prepared food for 250,000 strong, on the condition that the people who were fed would, in turn, serve others.

Had there been a quarter of a million hangry people, the iconic symbol of love, peace and cooperation could have turned into a muddy brawl. Woodstock could have been bereft of Kumbaya.

She also happened to take amazing photographs of the musicians of that time and continues, to this day, serving people more than just food.

How have you had so much access to rock stars, thinkers, and poets. What makes people trust you?

I wasn’t a photographer. I was just me. And I happened to have a camera.

I’m in service. I serve things. I’m working with the Native Americans to stop the relocation. I’m out there in the field. I’m in Arizona. I’m at the Hopi reservation. I’m at the Navajo reservation, helping them save their land because they were kicked off for Peabody Coal. I’m helping them and I’m photographing. I’m helping them, so they trust me.

How were you serving Bob Dylan?

I was his cook. I was his masseuse, and we went shopping together and we went out together. I happened to shoot a bunch of pictures of him while he was at my house. He stayed at my house, my castle.

Well evidently, you liked Bob Dylan, and he liked you.

I wasn’t just some hippie girl. I already had a job. I was part of the scene. I wasn’t an outsider.

He was extremely determined to write all the time. He could often be heard during the night typing away on his small typewriter. He was bent on drinking a lot of chocolate milkshakes so I took it on to fix him some good square meals which he loved. Many times after he had been writing all day and after dinner, I would give him a massage. He didn’t want me to let him fall asleep but he inevitably did. One day as he was descending the spiral staircase he told me he was going to marry Sara (which he did).

When Dylan played at the Paolo Soleri in Santa Fe in 1990, I hid under a Pendleton blanket in the 6th row and got a killer shot with him.

The last time I shot Dylan was in 2007 at the Journal Pavilion in Albuquerque. Lots of folks had little cameras but because I had a large one, I was spotted shooting by his guard backstage. Just then I felt a pair of hands on my shoulders and I was asked to follow him to the side of the stage. I was stuffing the roll into my waist band when he tried to stop me. I slapped his hand and told him not to touch me and asked him if he knew who I was. He didn’t and I giggled. He asked me for the roll and I told him it was back at my purse. He ended up with two empty rolls of 3200 black and white film and I had the photos.

Was that ambition or he just had to write something?

No, it was ambitious. He sat in this room and kept typing. When he was working, he would type up a song, but he never threw it away. He took it out of the typewriter, and he wrote on it. Every song he worked on, he added stuff to it with pencil. He channeled it.

Channeled it from where?

Bob says, I couldn’t write those songs anymore. It just came through me. Arlo Guthrie says, Oh, I could have channeled some of those. If God could have given me that, I would’ve channeled some of that. He gave them all to Bob Dylan.

He’s one of the few people could write like that. And that’s why he has all the awards he has and prizes, because of his literature. He’s a poet. It’s all poetry.

You also photographed Janis Joplin.

She and I met because I was doing a poster for her in San Francisco.

She had lots of guts to sing the way she sang. I mean, look how she sang at Monterey Pop. Everybody in the audience, especially The Mamas & the Papas are going, My God! She had a way of singing that was dynamic and it really moved people.

I met Janice in Taos at the La Fonda when she came to do a cigar commercial. And she grabs me and she’s hugging me and she said, Lisa, Lisa, you gotta help me, help me. And I said, Okay, well what can I do for you? She said, I’m tired of these city men. I want a mountain man!

I said, Come up to my house in Truchas. I’ll see if I can find you a mountain man.

So she came up and the mountain man I thought about was already there at my house. He just lived up the hill a little bit in a log cabin adobe thing.

So they went down to the little funky bar in Truchas. And the bartender set up a whole row of bottles and they drank them all. They were getting good and drunk. And that mountain man wasn’t just some mountain man. He was a pretty far out artist. But I don’t give his name to anybody.

Anyway, he says to her, Well, I got a potato baking in my wood stove up at my cabin up there. You wanna go up and check on that potato? And she goes, Okay.

So they go into his adobe house and they check on his potato and they make love all night! Afterwards, she’s walking up our driveway and she’s wearing her paisley dress and her fur jacket and her feather boa.

She went back to the airport. And that’s the last time I saw her. The next time I saw anything about her, she was dead.

Did it surprise you that she died?

Oh yeah, because I don’t believe she was an addict. I believe she simply OD’ed. She just wanted to feel good right then and there. She was waiting for a date and the date never showed up. She shot up too much.

Did she strike you as a happy person?

Yeah, she was happy. But I think she wanted a real relationship. She was very complicated, I don’t think she ever had what she really wanted.

Why did you come to New Mexico?

We came here in order to have our baby Pilar at the Birthing Center – the Catholic maternity birthing center on Delgado and Marcy.

New Mexico had the only center where there was natural childbirth. We came here with our teepee, set it up at New Buffalo and helped them build adobe houses.

We went to the Taos Pueblo and we got to meet Little Joe Gomez, who was the head of the Peyote Clan. And we got into Native Americans there and they always helped us figure out how to plant food on the land.

I was pretty hip to stuff like that. In Truchas, I grew all my own food. And I did all those herbs. I was working with healing people, taking care of people.

How did you happen to go to Woodstock?

In ‘69, they asked us to do Woodstock.

Who asked you?

Stan Goldstein and Michael Lang needed a group of people that do security and that take care of everybody on acid and to help out with tripping tents and help people manage themselves on the grounds. That was us, the Hog Farm.

They came and got us and took us in an empty American Airlines jet. There were 100 of us who flew into Kennedy Airport, and they drove us up to Woodstock. We brought Yogi Bhajan, too. Some people were so high on acid that they could barely tell you what was happening. I said, We gotta set up a real kitchen and food booth so we can feed people.

We went into New York and I bought 1200 pounds of bulgur wheat, 1200 pounds of rolled oats, sunflower seeds, wheat germ, dried apricots, almonds, currants, honey, and soy sauce. Then we bought 10 stoves, 10 stainless steel pots this big, giant steel bowls, onion cutters, cleavers, 35 trash cans to mix food in and 160,000 paper plates, 130,000 Dixie cups, spoons and forks.

We set up the kitchen and got it going. And had we not fed everybody, there would’ve been a different result at Woodstock.

So you helped save Woodstock?

Yeah, absolutely. And a lot of them say, I ate at the Hog Farm at Woodstock, and the Hog Farm changed my life! I became a vegan at the Hog Farm at Woodstock with their food. Now, they realize the Hog Farm was a very big deal. The Hog Farm that took care of everybody.

That’s one of the things I do, always. That’s why I work with the people in my museum in Yelapa, Mexico. I built a museum for free. I do everything for free. I help with the Native Americans and the relocation. We bring sheep to them. And I photograph all that. I love to do things like that.

It’s taking care of everybody. We have to help each other, help our neighbors, give them food. That’s what we need to get back to. And that’s what the 60s were about.

Learn more at flashingnthesixties.com

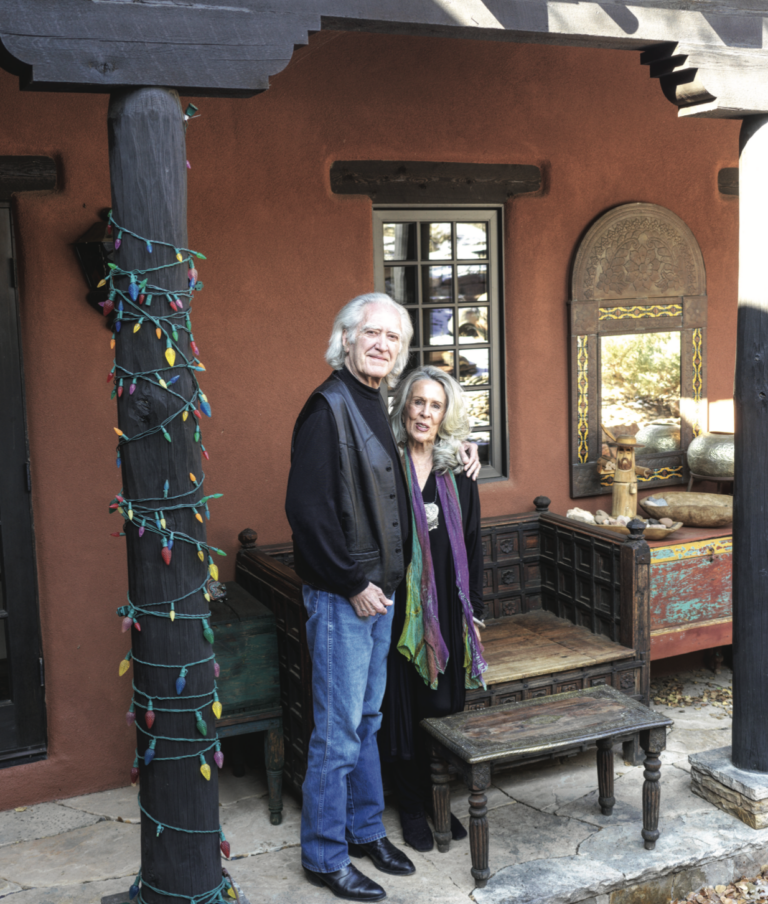

Photo Mark Berndt